Autor: Jean‑Pierre Revelly, Giorgio Iotti

Datum: 03.04.2023

In diesem Artikel werden die verschiedenen Komponenten der Mechanical Power, ihre Bedeutung in einer klinischen Situation und ihre Verwendung als Monitoring‑Parameter beleuchtet.

Diese Betrachtung beschränkt sich auf die Mechanical Power (MP) während der Inspirationsphase der kontrollierten Beatmung unter der Annahme, dass es keine Atembemühungen seitens des Patienten gibt.

Aus der Physik:

- Mechanische Arbeit ist die Energie, die verrichtet wird, wenn ein Körper durch eine Kraft von einer Position in eine andere bewegt wird.

- Die Leistung gibt an, welche Energiemengen in einer bestimmten Zeit umgesetzt werden.

Bei der maschinellen Beatmung ist die während der Inspiration vom Beatmungsgerät auf das Atemsystem übertrage Leistung eine übergeordnete Variable, in der die verschiedenen Elemente kombiniert sind, die eine beatmungsinduzierte Lungenschädigung (VILI) hervorrufen können (

Mechanical Power bei der CMV‑Beatmung

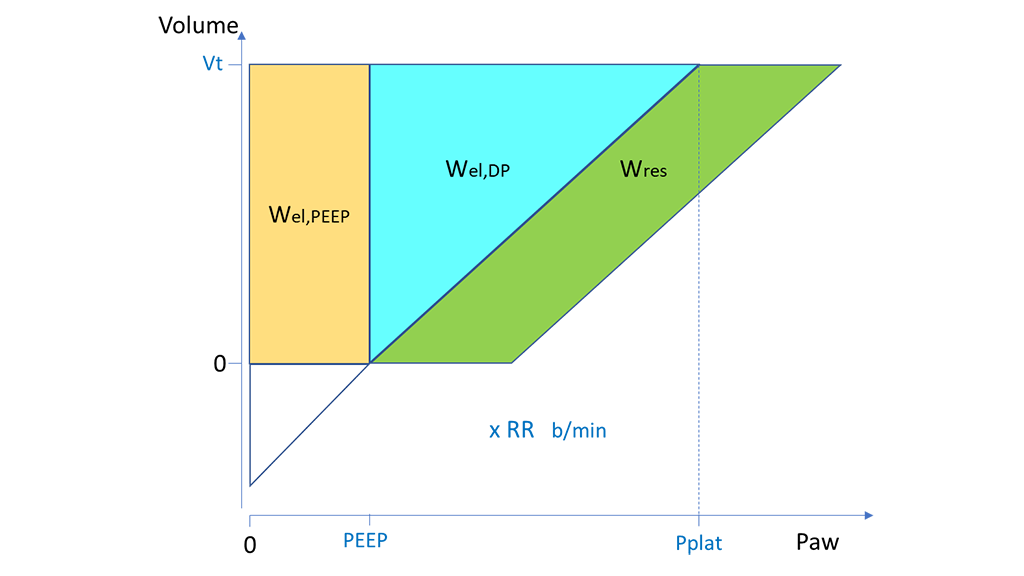

Bei der kontrollierten mandatorischen Beatmung (CMV) mit konstantem Flow kann MP ausgedrückt werden als Arbeit pro Atemhub (W) mal Atemfrequenz (AF) (Abbildung 1) (

Wobei gilt:

- Wel,PEEP entspricht der elastisch‑statischen Komponente, also der Komponente von MP, die sich auf PEEP bezieht.

- Wel,DP entspricht der (tidalen) elastisch‑dynamischen Komponente, also der Komponente von MP, die sich auf die Inspiration bezieht. Es wird mit einem rechtwinkligen Dreieck dargestellt. Dabei verkörpert die vertikale Seite das Tidalvolumen (Vt) und die horizontale Seite den Driving Pressure (DP). Die Steigung der dritten Seite entspricht der Compliance.

- Wres steht für die resistive Komponente, also die Energie, die bei jeder Inspiration abgeleitet wird, um die resistiven und viskosen Eigenschaften des Atemsystems zu überwinden. Wres wird mit einem Parallelogramm dargestellt. Dabei entspricht die Basis dem Unterschied zwischen dem Spitzendruck (Ppeak) und dem Plateaudruck (Pplat). Vt wird mit der Höhe ausgedrückt.

Mechanical Power bei der PCV‑Beatmung

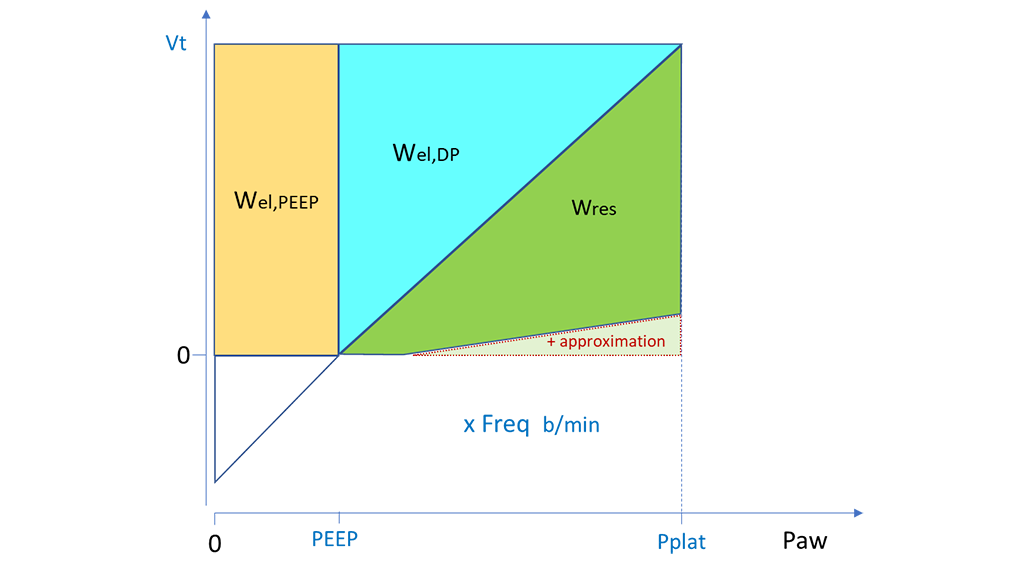

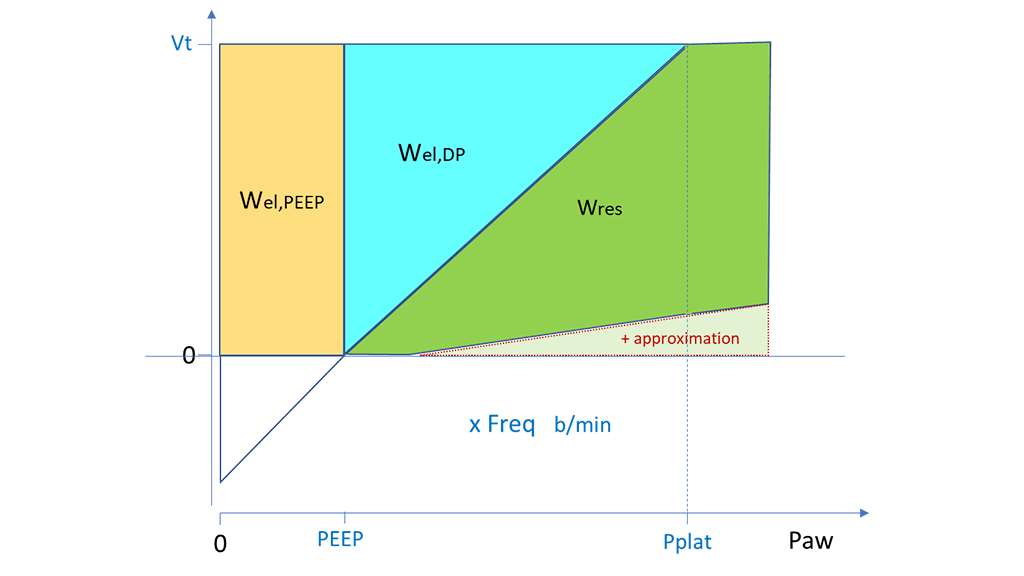

Ein ähnlicher Ansatz kann bei der druckkontrollierten Beatmung (PCV) für die Berechnung von Wel,PEEP und Wel,DP basierend auf Vt, PEEP und DP angewandt werden. Ein Näherungswert für Wres kann berechnet werden, indem die Fläche des Dreiecks mit Ppeak minus PEEP als Basis und Vt als Höhe errechnet und dann das Dreieck für Wel,DP abgezogen wird. Dieselbe Berechnung von Wres kann auch herangezogen werden, wenn Ppeak identisch mit Pplat ist (Abbildung 2) oder höher liegt (Abbildung 3), also wenn der endinspiratorische Flow null bzw. noch positiv ist. In beiden Fällen führt der Näherungswert zu einer leichten Überbewertung von Wres und somit der echten Gesamtarbeit des Beatmungsgerätes (

Ist die Mechanical Power klinisch relevant?

Zahlreiche Studienärzte haben Mechanical Power aus den Daten verschiedener Beatmungsstudien an Intensivpatienten mit (

Ergebnisse dieser Analysen:

- Nicht‑überlebende Patienten erhielten eine viel höhere MP als Überlebende

- Es bestand ein statistischer Zusammenhang zwischen einer steigenden MP und der Sterblichkeit auf der Intensivstation und im Krankenhaus, weniger Tagen ohne Beatmungsgerät und längeren Aufenthalten auf der Intensivstation und im Krankenhaus

Diese retrospektiven Studien legen insgesamt nahe, dass eine zu hohe Mechanical Power nach Möglichkeit vermieden werden sollte. Dieser Schlussfolgerung liegt die Annahme zugrunde, dass ein schlechteres klinisches Behandlungsergebnis teilweise auf VILI zurückzuführen ist.

Gibt es einen sicheren MP‑Wert für alle Patienten?

Die Methoden, die zur Berechnung der MP in veröffentlichten Studien verwendet wurden, müssen genau betrachtet werden, um eine korrekte Interpretation zu ermöglichen. Je nach Verfügbarkeit der Daten ist es möglich, dass die Autoren diverse Komponenten der MP nicht berücksichtigt haben. Es ist auch umstritten, welche Methode zum Vergleichen der verschiedenen Patienten am besten geeignet ist. Ein Vorschlag umfasst eine Normalisierung der Größe des Patienten (voraussichtliches Körpergewicht), der Compliance oder des endexspiratorischen Lungenvolumens.

Generell ist zu beachten, dass es noch keinen standardisierten Ansatz für die Berechnung der MP gibt. Ebenso wurde kein weithin akzeptierter sicherer Wert für die geschätzte MP definiert.

Ist die Mechanical Power für eine kontinuierliche Überwachung geeignet?

Individuelle Änderungen an den Einstellungen am Beatmungsgerät haben komplexe Auswirkungen auf andere Variablen der Beatmungsmechanik. Das Konzept der Mechanical Power beruht auf der implizierten Annahme, dass alle Beatmungsvariablen ein lineares Verhältnis zueinander haben und gleichermaßen zur VILI beitragen. Dies trifft jedoch nicht zu, wie am Beispiel von PEEP zu erkennen ist, dessen Verhältnis zur VILI kurvenförmig (J‑Form) ist (

Wenn auch eine Reihe von Fragen unbeantwortet bleibt, dürfte es nützlich sein, die Gesamt‑MP und ihre Komponenten zu überwachen, um die Entwicklung des einzelnen Patienten oder seine Reaktion auf Änderungen in den Beatmungseinstellungen zu bewerten. Die Mechanical Power könnte ein weiterer Faktor neben anderen Komponenten bei der klinischen Bewertung und Entscheidungsfindung werden. Zudem würde die Überwachung der MP das Sammeln hochqualitativer Daten für zukünftige prospektive Studien zum Verhältnis zwischen MP und VILI bedeutend fördern.

Wie können wir also das Risiko einer VILI mit den Beatmungseinstellungen verringern?

Verschiedene Studienärzte haben versucht, die schädlichsten Komponenten der Beatmung zu identifizieren. Eine retrospektive Studie fasste die Beatmungsdaten von 4.500 ARDS‑Patienten, die an kontrollierten Studien teilgenommen hatten, zusammen und beurteilte mit multivariablen Modellen das Verhältnis von MP, Vt, AF und DP zur 28‑Tage‑Sterblichkeit (

Es kommt wenig überraschend, dass die Autoren einen Zusammenhang zwischen der Gesamt‑MP und der Sterblichkeit fanden. Bei der Beurteilung der verschiedenen Komponenten der MP war nur die elastisch‑dynamische Komponente (MPel,DP, also MP in Abhängigkeit von Wel,DP) statistisch relevant; die von PEEP oder der Resistance abhängigen Komponenten waren statistisch nicht relevant. MPel,DP ist bei der CMV‑ wie bei der PCV‑Beatmung besonders einfach am Patientenbett zu ermitteln.

- MPel,DP = Vt x DP x AF / 2

Die Autoren fanden eine ähnliche Prädiktivität der Sterblichkeit, indem sie einfach DP und AF in folgendem Index vereinten:

- 4DP+AF Index = (4 x DP) + AF

Die Autoren kamen zu folgendem Schluss: „Wenn auch die Mechanical Power mit der Sterblichkeit bei ARDS‑Patienten in Verbindung stand, so gaben ∆P und AF ebenso viel Aufschluss und konnten am Patientenbett leichter bestimmt werden. Ob eine Beatmungsstrategie auf Basis dieser Variablen das Behandlungsergebnis positiv beeinflusst, muss in randomisierten Studien geprüft werden“ (

Fußnoten

Referenzen

- 1. Gattinoni L, Tonetti T, Cressoni M, et al. Ventilator‑related causes of lung injury: the mechanical power. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1567‑1575. doi:10.1007/s00134‑016‑4505‑2

- 2. Costa ELV, Slutsky AS, Brochard LJ, et al. Ventilatory Variables and Mechanical Power in Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(3):303‑311. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009‑3467OC

- 3. Becher T, van der Staay M, Schädler D, Frerichs I, Weiler N. Calculation of mechanical power for pressure‑controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(9):1321‑1323. doi:10.1007/s00134‑019‑05636‑8

- 4. Tonna JE, Peltan I, Brown SM, Herrick JS, Keenan HT; University of Utah Mechanical Power Study Group. Mechanical power and driving pressure as predictors of mortality among patients with ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(10):1941‑1943. doi:10.1007/s00134‑020‑06130‑2

- 5. Coppola S, Caccioppola A, Froio S, et al. Effect of mechanical power on intensive care mortality in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):246. Published 2020 May 24. doi:10.1186/s13054‑020‑02963‑x

- 6. Serpa Neto A, Deliberato RO, Johnson AEW, et al. Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in critically ill patients: an analysis of patients in two observational cohorts. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(11):1914‑1922. doi:10.1007/s00134‑018‑5375‑6

- 7. Robba C, Badenes R, Battaglini D, et al. Ventilatory settings in the initial 72 h and their association with outcome in out‑of‑hospital cardiac arrest patients: a preplanned secondary analysis of the targeted hypothermia versus targeted normothermia after out‑of‑hospital cardiac arrest (TTM2) trial. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(8):1024‑1038. doi:10.1007/s00134‑022‑06756‑4

- 8. van Meenen DMP, Algera AG, Schuijt MTU, et al. Effect of mechanical power on mortality in invasively ventilated ICU patients without the acute respiratory distress syndrome: An analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2023;40(1):21‑28. doi:10.1097/EJA.0000000000001778

- 9. Marini JJ, Rocco PRM. Which component of mechanical power is most important in causing VILI?. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):39. Published 2020 Feb 5. doi:10.1186/s13054‑020‑2747‑4

- 10. Marini JJ, Crooke PS, Gattinoni L. Intra‑cycle power: is the flow profile a neglected component of lung protection?. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(5):609‑611. doi:10.1007/s00134‑021‑06375‑5

- 11. Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):747‑755. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1410639