Autore: Dr. med. Jean-Michel Arnal, Senior Intensivist, Hopital Sainte Musse, Toulon, France

Data: 30.08.2017

The recocommendations issued by the American Thoracic Society and the American College of Chest Physicians suggest using a ventilator liberation protocol and performing spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs) with modest inspiratory pressure support (5-8 cmH2O) (

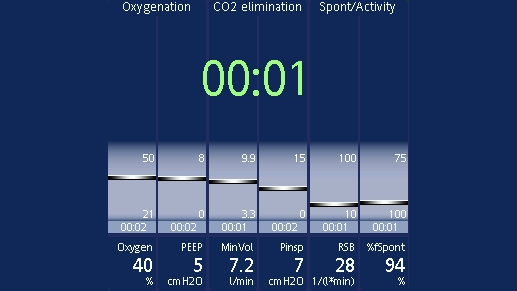

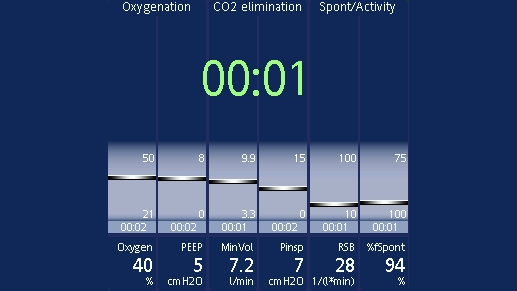

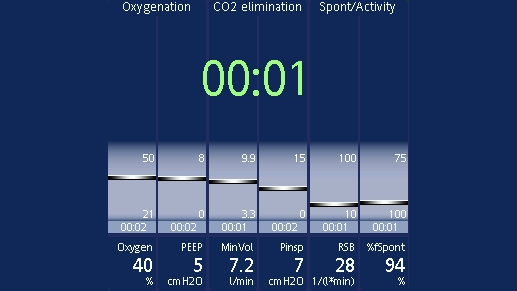

The following parameters are constantly screened and displayed in the Vent Status panel (

You can set the thresholds yourself in configuration. The range of values in between (shown in light blue) is known as the weaning zone. In short-term ventilated patients, you can use these parameters as a guide for extubation. In long-term ventilated patients, the parameters indicate when you can consider performing an SBT.

When all the values are within this set range, the timer appears and shows you how long the patient has been in the weaning zone for. If a parameter moves out of the weaning zone for longer than two minutes, the timer will reset to 00:00.

Other non-respiratory weaning criteria also need to be screened at the bedside. These are:

If all these conditions are fulfilled, you can start an SBT.

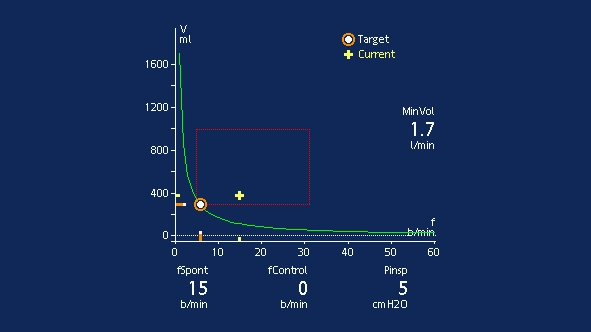

You can carry out an SBT in ASV by decreasing PEEP to 5 cmH2O and lowering the target minute volume (%MinVol) setting to reduce the pressure support as needed. If the pressure support on the current %MinVol setting is higher than 15 cmH2O, the %MinVol setting can be lowered first to 70% and then 25% to reduce pressure support gradually to 5-8 cmH2O for the SBT.

The patient should be monitored both clinically and using the Vent Status panel. Clinical monitoring includes neurological status, effort to breathe, heart rate, and arterial blood pressure. Respiratory monitoring includes SpO2, PetCO2, respiratory rate, and tidal volume. Patient exhaustion may lead to an increase in the respiratory rate with a small tidal volume, and cause an increase in pressure support according to the ASV algorithm.

If the patient remains stable for 30 minutes, you can consider extubation (