Personal Communication Device Use by Nurses Providing In‑Patient Care: Survey of Prevalence, Patterns, and Distraction Potential.

McBride DL, LeVasseur SA. Personal Communication Device Use by Nurses Providing In‑Patient Care: Survey of Prevalence, Patterns, and Distraction Potential. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017;4(2):e10. Published 2017 Apr 13. doi:10.2196/humanfactors.5110

BACKGROUND

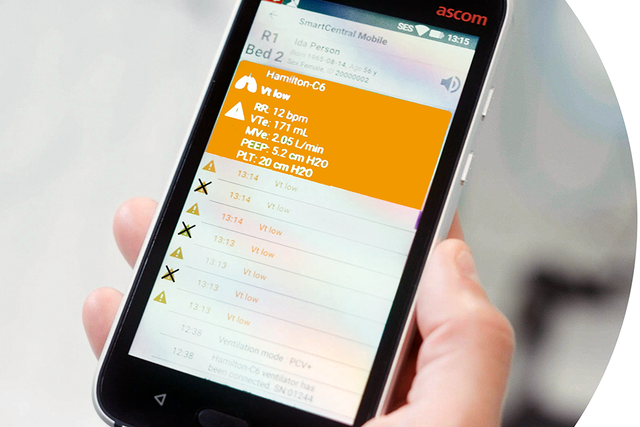

Coincident with the proliferation of employer‑provided mobile communication devices, personal communication devices, including basic and enhanced mobile phones (smartphones) and tablet computers that are owned by the user, have become ubiquitous among registered nurses working in hospitals. While there are numerous benefits of personal communication device use by nurses at work, little is known about the impact of these devices on in‑patient care.

OBJECTIVE

Our aim was to examine how hospital-registered nurses use their personal communication devices while doing both work-related and non‒work-related activities and to assess the impact of these devices on in-patient care.

METHODS

A previously validated survey was emailed to 14,797 members of two national nursing organizations. Participants were asked about personal communication device use and their opinions about the impact of these devices on their own and their colleagues' work.

RESULTS

Of the 1268 respondents (8.57% response rate), only 5.65% (70/1237) never used their personal communication device at work (excluding lunch and breaks). Respondents self-reported using their personal communication devices at work for work-related activities including checking or sending text messages or emails to health care team members (29.02%, 363/1251), as a calculator (25.34%, 316/1247), and to access work-related medical information (20.13%, 251/1247). Fewer nurses reported using their devices for non‒work-related activities including checking or sending text messages or emails to friends and family (18.75%, 235/1253), shopping (5.14%, 64/1244), or playing games (2.73%, 34/1249). A minority of respondents believe that their personal device use at work had a positive effect on their work including reducing stress (29.88%, 369/1235), benefiting patient care (28.74%, 357/1242), improving coordination of patient care among the health care team (25.34%, 315/1243), or increasing unit teamwork (17.70%, 220/1243). A majority (69.06%, 848/1228) of respondents believe that on average personal communication devices have a more negative than positive impact on patient care and 39.07% (481/1231) reported that personal communication devices were always or often a distraction while working. Respondents acknowledged their own device use negatively affected their work performance (7.56%, 94/1243), or caused them to miss important clinical information (3.83%, 47/1225) or make a medical error (0.90%, 11/1218). Respondents reported witnessing another nurse's use of devices negatively affect their work performance (69.41%, 860/1239), or cause them to miss important clinical information (30.61%, 378/1235) or make a medical error (12.51%, 155/1239). Younger respondents reported greater device use while at work than older respondents and generally had more positive opinions about the impact of personal communication devices on their work.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of registered nurses believe that the use of personal communication devices on hospital units raises significant safety issues. The high rate of respondents who saw colleagues distracted by their devices compared to the rate who acknowledged their own distraction may be an indication that nurses are unaware of their own attention deficits while using their devices. There were clear generational differences in personal communication device use at work and opinions about the impact of these devices on patient care. Professional codes of conduct for personal communication device use by hospital nurses need to be developed that maximize the benefits of personal communication device use, while reducing the potential for distraction and adverse outcomes.