Autore: Clinical Experts Group, Hamilton Medical

Data: 30.09.2020

Last change: 30.09.2020

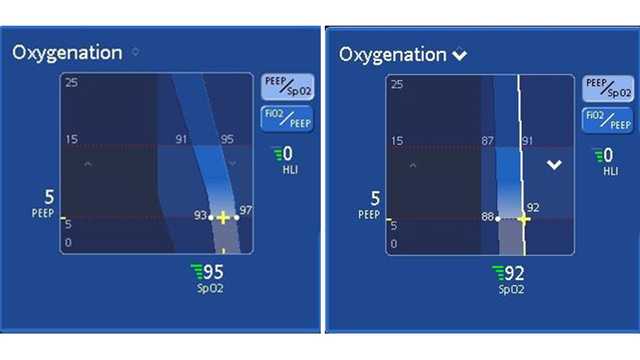

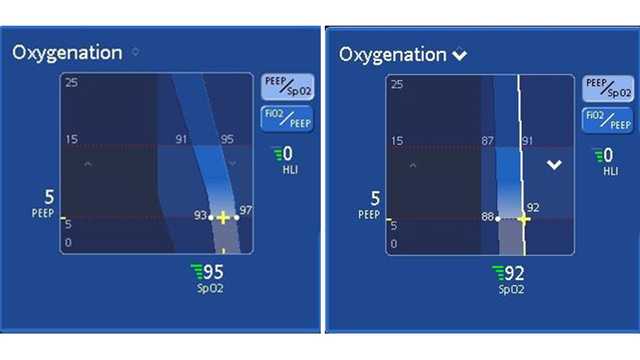

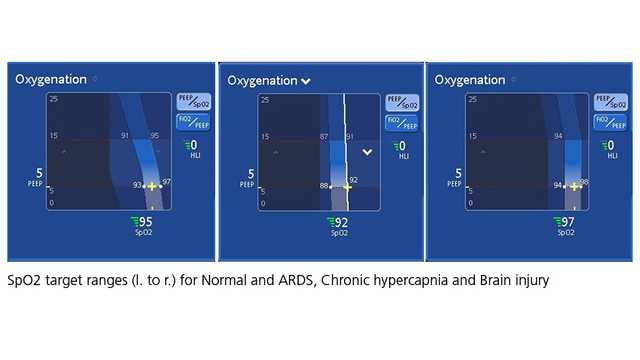

(Originally published 30.08.2017) Previously: chronic hypercapnia range 88-93%; brain injury range 96-99%. New screenshots.

When using INTELLiVENT®-ASV® (

Full citations below: (